Here's a scenario that keeps many campus leaders up at night: they've invested significantly in security infrastructure—cameras, card access, emergency phones—yet student surveys still show troubling numbers around feeling unsafe. The disconnect isn't about equipment. It's about approach.

When safety efforts focus exclusively on incident prevention while ignoring the psychological and emotional dimensions of security, institutions miss the point entirely. Students don't just need to be safe. They need to feel safe. And that feeling—or its absence—directly shapes their mental health, academic performance, and likelihood of staying enrolled.

Here's the truth: comprehensive safety planning and trauma-informed practices don't just reduce risk. They create the conditions where students can actually thrive.

Key Takeaways

Campus safety directly impacts student mental health, belonging, and retention

Trauma-informed approaches require systemic change, not just policy updates

Effective safety planning integrates physical, emotional, and psychological dimensions

Measurable outcomes include reduced incidents, improved help-seeking behavior, and higher persistence rates

Perceived safety matters as much as actual safety metrics—students need to feel secure, not just be told they are

Why Campus Safety Is a Wellbeing Issue

Let's start with what the data tells us. According to the American College Health Association's National College Health Assessment, students who report feeling unsafe on campus are significantly more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and academic difficulties [1]. The connection isn't coincidental—it's causal.

When students operate in survival mode, their cognitive resources get redirected from learning to threat detection. Psychologists call this hypervigilance, and it's exhausting. A student scanning the quad for potential threats isn't fully present in their biology lecture. A student who can't sleep because their residence hall feels insecure isn't performing well on exams.

Translation? Safety concerns create a tax on student success that compounds over time.

This matters particularly for historically marginalized students. Research from the Association of American Universities found that students of color, LGBTQ+ students, and students with disabilities report higher rates of campus safety concerns and are more likely to experience the wellbeing consequences [2]. When we talk about equity in student success, campus safety has to be part of that conversation.

The Gap Between Spending and Feeling

Many institutions face an uncomfortable paradox: security budgets grow while student perceptions of safety remain flat or decline. This happens when investments prioritize visible deterrents (more cameras, more patrols) without addressing the underlying experience of safety.

A 2019 NASPA research brief on campus safety climate found that students' sense of security depends heavily on factors beyond physical infrastructure—including trust in institutional response, perceived care from staff, and confidence that reporting will lead to meaningful action [3]. In other words, students assess safety based on relationships and responsiveness, not just hardware.

For campus leaders evaluating current approaches, this insight is critical: the ROI of safety investments depends on whether students actually engage with and trust those systems.

What Comprehensive Safety Planning Actually Looks Like

Effective campus safety isn't a single initiative or a new camera system. It's an integrated approach that addresses multiple dimensions of student experience.

Physical Safety Infrastructure

The basics matter: lighting, locks, emergency call stations, secure building access. But physical infrastructure only works when it's designed with student behavior in mind. A blue light emergency phone placed where students don't actually walk at night is security theater, not security.

Smart safety planning involves:

Conducting regular safety audits with student input

Analyzing incident data to identify hotspots and patterns

Ensuring accessibility so all students can use safety resources

Maintaining and testing systems consistently, not just installing them

The Clery Center recommends that institutions involve students directly in safety audits, noting that students often identify vulnerabilities that facilities staff miss—like poorly lit shortcuts between buildings or residence hall entry points with broken locks [4].

Psychological Safety Systems

Physical safety addresses external threats. Psychological safety addresses the internal experience of feeling protected, respected, and able to take interpersonal risks without fear of humiliation or harm.

On a psychologically safe campus, students feel comfortable:

Reporting concerns without fear of retaliation

Seeking help for mental health challenges

Disclosing experiences of harassment or assault

Making mistakes in learning environments without shame

Creating psychological safety requires attention to policies, practices, and culture simultaneously. A robust reporting system means nothing if students believe nothing will happen when they use it.

Research published in the Journal of College Student Development indicates that students who perceive high psychological safety on campus report stronger sense of belonging and are more likely to persist through academic challenges [5]. This suggests that psychological safety functions as a protective factor for retention—not just wellbeing.

Emergency Preparedness and Communication

How a campus responds to crises—and how it communicates before, during, and after—shapes student perceptions of safety for years. Clear protocols, regular drills that don't traumatize participants, and transparent communication build trust.

Students should know:

What to do in various emergency scenarios

How they'll be notified of threats

Where to find support after incidents

That the institution takes their safety seriously enough to prepare

The U.S. Department of Education's guidance on emergency management planning emphasizes that effective communication is as important as response protocols. Institutions that communicate proactively and transparently during and after incidents see faster recovery of student trust [6].

Trauma-Informed Practices: Moving Beyond Policy

Here's where many institutions get stuck. They update policies, install technology, and check compliance boxes—but they don't fundamentally shift how the campus operates. Trauma-informed practice requires deeper work.

Understanding Trauma's Prevalence

A significant percentage of college students arrive on campus having already experienced trauma. Research published in Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy found that over 60% of college students have experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, with many experiencing multiple traumas [7]. These experiences don't disappear at orientation.

When campus environments inadvertently trigger trauma responses—through aggressive security practices, dismissive responses to disclosures, or chaotic crisis communication—they compound existing harm rather than promoting healing.

The SAMHSA Framework Applied to Higher Education

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) outlines six key principles for trauma-informed approaches: safety, trustworthiness and transparency, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, empowerment and choice, and cultural responsiveness [8]. Translating these principles into campus practice looks like:

Safety: Creating environments that feel physically and emotionally secure—calm spaces, predictable routines, clear communication.

Trustworthiness: Doing what you say you'll do. Following up on reports. Being transparent about processes and limitations.

Peer Support: Leveraging student leaders, RAs, and peer mentors as first responders who can recognize distress and connect students to resources.

Collaboration: Including students in designing safety initiatives rather than imposing solutions on them.

Empowerment: Giving students choices in how they receive support and restoring agency after disempowering experiences.

Cultural Responsiveness: Recognizing that different communities experience safety differently and designing approaches that account for those differences.

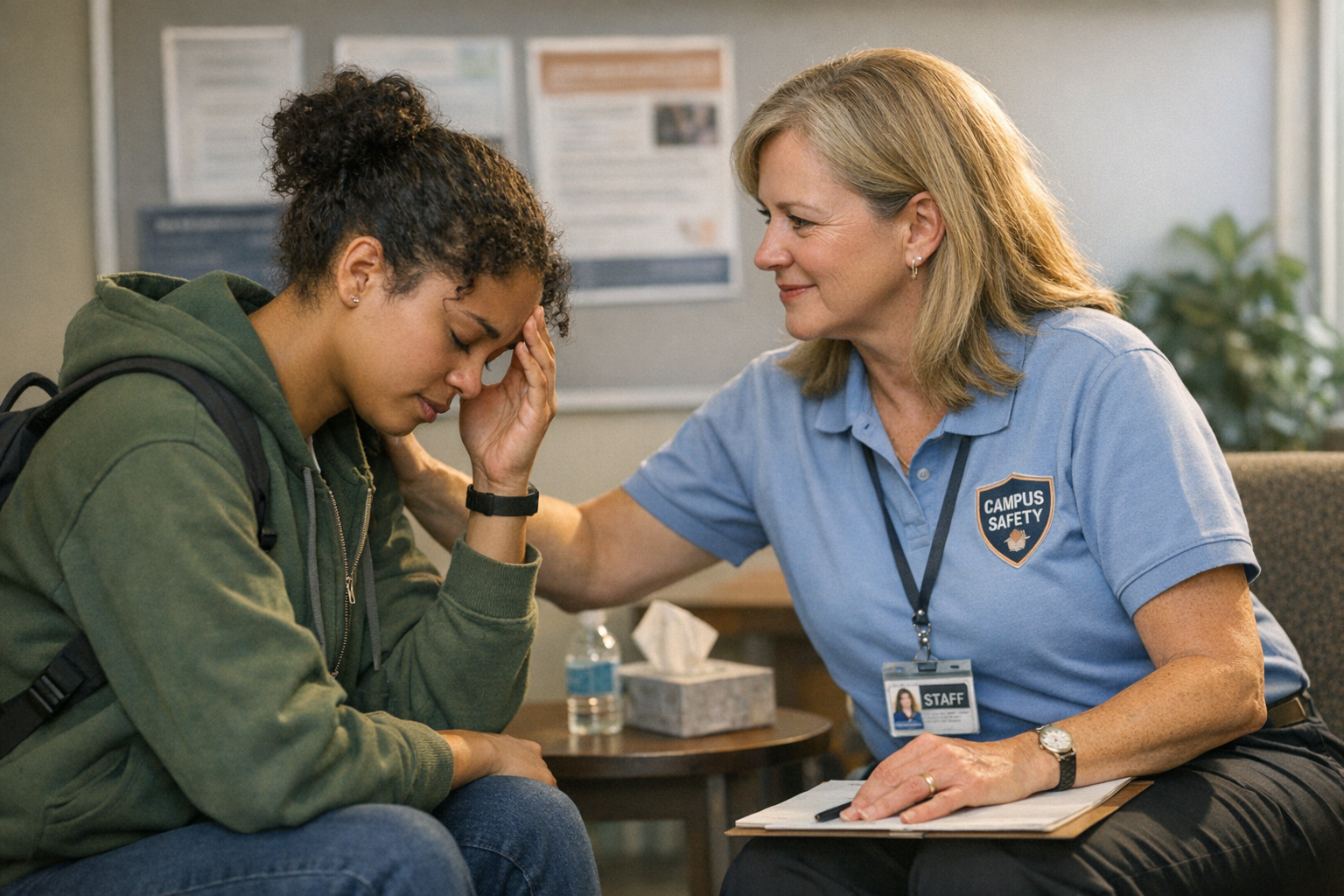

Training Staff Across the Institution

Trauma-informed practice can't live solely in the counseling center. Every staff member who interacts with students needs foundational understanding of:

How trauma affects brain function and behavior

The difference between trauma-informed responses and traditional approaches

Techniques for de-escalation and supportive communication

Self-care strategies to prevent secondary traumatic stress

This includes residence life staff, campus police, dining services workers, faculty, and administrative personnel. The student who discloses a safety concern to a maintenance worker deserves the same informed response as one who visits the counseling center.

Practical training options include:

Mental Health First Aid: An evidence-based program teaching non-clinical staff to recognize and respond to mental health crises [9]

Kognito simulations: Interactive role-play scenarios that build skills in recognizing distress and having supportive conversations [10]

QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer): Gatekeeper training focused on suicide prevention that translates well to broader crisis response

The key is ongoing professional development, not one-time workshops. Building trauma-informed capacity requires practice, reinforcement, and accountability.

Creating Physically and Emotionally Safe Spaces

Designated safe spaces serve multiple functions on trauma-informed campuses:

Quiet rooms where students can decompress during overwhelming moments

Identity-based centers where marginalized students find community

Confidential reporting locations that prioritize survivor agency

Accessible mental health services with minimal barriers

The design of these spaces matters. Trauma-informed environments tend to feature natural light, comfortable seating, clear sightlines to exits, and calm color palettes. These aren't aesthetic preferences—they're evidence-based approaches to reducing physiological stress responses.

Survivor-Centered Response Protocols

When incidents do occur, how the institution responds determines whether students feel supported or retraumatized. Survivor-centered approaches prioritize:

Believing and validating student experiences

Providing choices and restoring agency

Connecting students with appropriate resources without overwhelming them

Following up consistently over time

Avoiding victim-blaming language in all communications

This doesn't mean abandoning due process or accountability. It means designing systems that can hold both survivor support and fair processes simultaneously. The Title IX Resource Center provides guidance on building response protocols that meet both legal requirements and survivor needs [11].

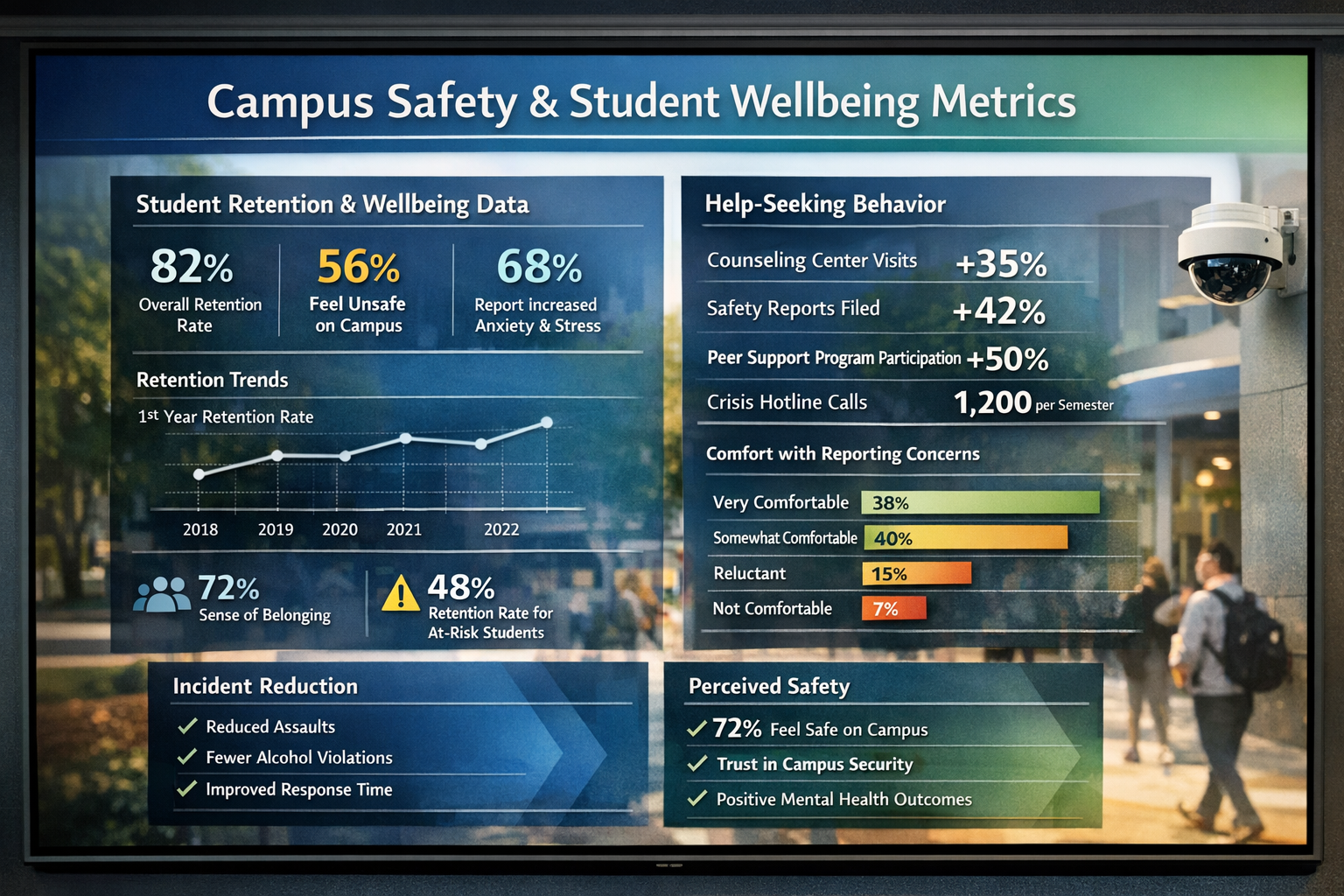

Measuring What Matters: Success Metrics for Safe Campuses

How do you know if your safety initiatives are actually working? Incident counts alone don't tell the full story—in fact, increased reporting can indicate greater trust in the system rather than declining safety.

Incident and Response Metrics

Track not just what happens, but how you respond:

Time from report to initial response

Resolution rates for various incident types

Recidivism rates for perpetrators

Student satisfaction with response processes

A note on interpretation: Rising report numbers aren't necessarily bad news. Institutions that implement trauma-informed reporting processes often see initial increases in disclosures as students feel more comfortable coming forward. This is a sign of trust, not failure.

Help-Seeking Behavior

When students trust campus safety systems, they use them. Monitor:

Utilization rates of counseling services

Reports to campus security (anonymous and identified)

Engagement with bystander intervention programs

Participation in safety-related training and events

Increasing utilization often signals that students feel safer seeking help, not that more students need it.

Climate and Perception Data

Regular climate surveys provide insight into the subjective experience of safety:

Percentage of students who feel safe in various campus locations

Trust levels in campus police and security

Comfort with reporting mechanisms

Perceived institutional commitment to safety

Disaggregate this data by student demographics to identify disparities in safety perception across groups. The AAU Campus Climate Survey provides a validated instrument for measuring these dimensions [2].

Retention and Success Correlations

The ultimate test: do students who feel safe stay enrolled and succeed?

Retention rates correlated with campus safety perceptions

Academic performance patterns for students who report safety concerns

Graduation rates across safety climate indicators

Sense of belonging scores connected to safety experiences

Research from the Education Advisory Board suggests that institutions implementing comprehensive safety and wellbeing initiatives often see measurable improvements in first-year retention, particularly among students from historically marginalized populations who may face elevated safety concerns [12].

Connecting Safety to Broader Student Success

Campus safety doesn't operate in isolation. It intersects with every other dimension of student wellbeing and institutional effectiveness.

Mental Health Integration

Safety concerns and mental health challenges often co-occur and reinforce each other. Students experiencing anxiety may perceive greater threat in their environment. Students who've experienced campus-based trauma may develop depression, PTSD, or substance use issues.

Effective approaches integrate safety and mental health services rather than siloing them. This might look like:

Counselors trained in trauma-specific interventions

Collaborative case management between security and student affairs

Proactive outreach to students who've reported safety concerns

Mental health resources embedded in safety response protocols

Belonging and Community

Students who feel unsafe often withdraw from campus life, missing the social connections that support persistence. Conversely, strong community bonds can increase perceptions of safety through informal networks of mutual support.

Safety initiatives that build community—like peer-led bystander intervention programs or residence hall floor meetings about healthy community norms—serve dual purposes. Programs like Green Dot and Step UP! have shown effectiveness in both reducing incidents and strengthening campus community [13].

Academic Engagement

When basic safety needs are met, students can direct attention toward learning. Faculty who understand trauma-informed teaching practices create classrooms where all students can participate fully, even those carrying difficult experiences.

This isn't about lowering standards. It's about removing unnecessary barriers so students can meet high expectations.

Your Next Steps (Yes, Today)

Whether you're a campus leader evaluating your current approach or an administrator beginning to explore trauma-informed practices, here's where to start:

Assess your current state honestly. Conduct a comprehensive safety audit that includes student voice, not just facilities inspection. Survey students about perceived safety across locations, times, and situations. Identify gaps between policy and practice.

Invest in training at scale. Start with staff who interact most frequently with students—residence life, campus police, first-year experience coordinators—then expand systematically. One-time workshops aren't sufficient; build ongoing professional development into job expectations.

Design with students, not just for them. Include students in safety planning processes. They know where they feel unsafe and why. They can identify barriers to reporting that administrators might miss. Their buy-in increases program effectiveness.

Measure what matters and act on findings. Establish baseline metrics, track progress over time, and disaggregate data to identify disparities. When data reveals problems, respond visibly and communicate what you're doing.

Connect safety to retention strategy. Stop treating safety as a compliance function separate from student success. Integrate safety considerations into retention planning, and include safety metrics in institutional effectiveness reporting.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does campus safety directly affect student mental health?

Students who perceive their campus as unsafe experience elevated stress responses that interfere with sleep, concentration, and emotional regulation. Over time, chronic safety concerns contribute to anxiety, depression, and burnout. Research consistently links safety perceptions to mental health outcomes, with students who feel unsafe reporting significantly higher rates of psychological distress and academic difficulties [1]. The relationship is bidirectional—mental health challenges can also heighten perceived threat.

What does trauma-informed practice mean in a campus context?

Trauma-informed practice means designing systems, training staff, and creating environments that recognize the prevalence of trauma, understand its effects, and avoid retraumatization. It shifts from asking "what's wrong with you?" to "what happened to you?" SAMHSA's framework emphasizes six principles: safety, trustworthiness, peer support, collaboration, empowerment, and cultural responsiveness [8]. Applied to campuses, this means everything from how security officers approach students to how reporting systems are designed.

Can improved safety policies actually increase retention rates?

Evidence suggests yes. Students who feel safe and supported are more likely to persist through challenges and graduate. The Education Advisory Board reports that institutions implementing comprehensive safety and wellbeing initiatives often see measurable improvements in first-year retention, particularly among students from marginalized backgrounds who may face elevated safety concerns [12]. The mechanism is straightforward: when students aren't expending cognitive resources on threat detection, they have more capacity for learning and engagement.

How should campuses balance security measures with creating a welcoming environment?

The goal is security that empowers rather than intimidates. This means involving students in planning, prioritizing visible but approachable security presence, ensuring safety measures are accessible to all students, and communicating the purpose behind security practices. When students understand that safety measures exist to protect them—not control them—they're more likely to view security positively. Community policing models that emphasize relationship-building over enforcement tend to achieve this balance more effectively.

What role do faculty and staff outside student affairs play in campus safety?

Every employee who interacts with students shapes safety culture. Faculty may be the first to notice a student in distress. Maintenance workers may receive disclosures. Administrative staff set tones in their offices. Training the entire campus community in trauma-informed response ensures students receive consistent, supportive treatment regardless of where they seek help. This distributed approach also reduces burden on counseling centers by creating multiple pathways to support.

Creating Campuses Where Students Can Thrive

Safe campuses don't happen by accident. They result from intentional planning, sustained investment, and genuine commitment to student wellbeing as a foundational institutional value.

The students walking across your campus tonight are carrying experiences, concerns, and hopes you may never know about. Some are navigating trauma. Some are weighing whether this is a place they can succeed. All of them deserve environments where safety is a given, not a question.

When institutions get this right, the returns extend far beyond reduced incident reports. Students engage more deeply. They persist through challenges. They graduate prepared to contribute to communities that need their talents.

That's the real ROI of linking safety policies to student wellbeing.

Ready to build a more connected, supportive campus environment? Book a call with CampusMind to explore how integrated engagement and wellbeing tools can support your safety and retention goals.

About This Resource

This guide was developed by the CampusMind Insights team, which specializes in evidence-based strategies for student engagement, wellbeing, and retention in higher education. Our recommendations draw from current research, institutional best practices, and direct experience supporting colleges and universities across the United States. CampusMind's platform helps institutions connect students to resources, track engagement patterns, and intervene early—core components of comprehensive campus safety and wellbeing strategy.

Works Cited

[1] American College Health Association — "National College Health Assessment: Reference Group Executive Summary." https://www.acha.org/NCHA/ACHA-NCHA_Data/Publications_and_Reports/NCHA/Data/Reports_ACHA-NCHAIII.aspx

[2] Association of American Universities — "Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct." https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/Revised%20Aggregate%20report%20%20and%20target.pdf

[3] NASPA Research and Policy Institute — "Campus Safety Climate: Dimensions of Student Trust and Reporting Behavior." https://www.naspa.org/publications

[4] Clery Center for Security on Campus — "Campus Safety Audit Guide." https://clerycenter.org/resources/

[5] Reason, R.D., Terenzini, P.T., & Domingo, R.J. — "Developing Social and Personal Competence in the First Year of College." Review of Higher Education. https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/172

[6] U.S. Department of Education — "Guide for Developing High-Quality Emergency Operations Plans for Institutions of Higher Education." https://www.ed.gov/emergency-plan-guide-higher-ed

[7] Read, J.P., Ouimette, P., White, J., Colder, C., & Farrow, S. — "Rates of DSM–IV–TR Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Newly Matriculated College Students." Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-14816-001

[8] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — "SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach." https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884

[9] Mental Health First Aid USA — "About the Program." https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/about/

[10] Kognito — "Higher Education Solutions." https://kognito.com/solutions/higher-education

[11] Title IX Resource Center — "Trauma-Informed Response Guidelines." https://www.titleix.info/

[12] Education Advisory Board — "Student Success Collaborative Research." https://eab.com/research/

[13] Coker, A.L., et al. — "Evaluation of Green Dot: An Active Bystander Intervention to Reduce Sexual Violence on College Campuses." Violence Against Women. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/vaw