"Will I make it through college?"

A first-year student asked me that last week during advising hours. Not "Can I pass calculus?" or "Should I switch majors?" Just the raw question underneath everything else: Will I make it?

The answer used to be murky—a mix of intuition, anecdote, and hope. Not anymore. After tracking millions of students through the National Student Clearinghouse and analyzing retention patterns across hundreds of institutions, researchers know exactly what separates students who finish from those who leave. Only 62% of students starting at four-year institutions graduate within six years, but understanding the predictors can dramatically shift those odds in your favor.

Success isn't about being the smartest person in lecture halls. The data on student success points to five factors that matter far more than test scores or natural ability.

The First-Year Threshold That Changes Everything

Students who complete freshman year have an 86% chance of returning for sophomore year. Cross that threshold, and completion becomes likely. But here's the catch: one in four first-time students won't make it past that first year. For more insights into why, explore college dropout reasons.

Those initial months operate like a sorting mechanism. You're either building the scaffolding—social networks, academic routines, the courage to ask for help—or discovering the gaps in real time. High school ran on bells and schedules and someone always checking whether you showed up. College hands you a syllabus and says "figure it out." Students who make that cognitive shift early tend to persist. Those who don't often disappear quietly over winter break, before anyone thought to intervene.

The National Center for Education Statistics confirms what advisors witness: early disengagement predicts departure. Missing those first-semester connections creates a spiral. You skip one club meeting, then another. You stop going to office hours. You study alone. Eventually you're attending class like a ghost—physically present but disconnected from everything that makes college work.

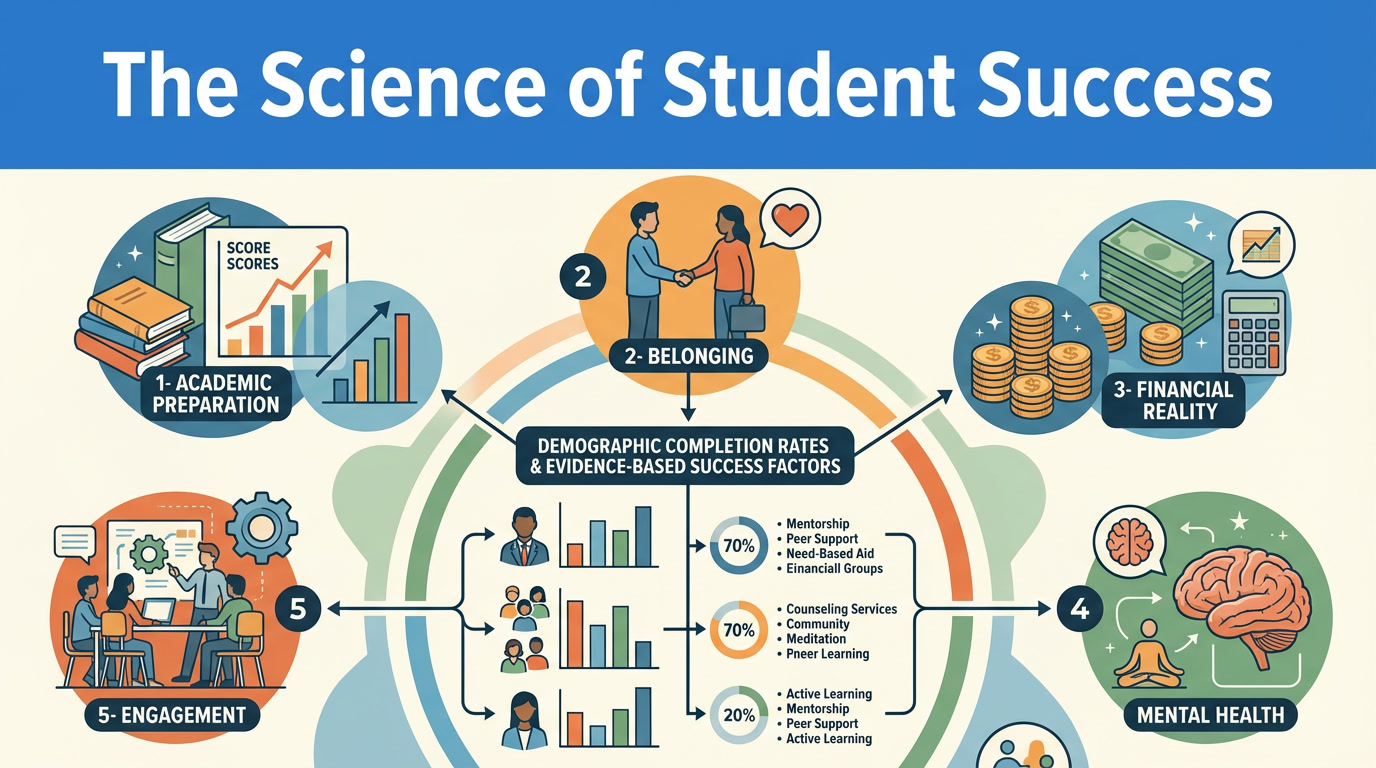

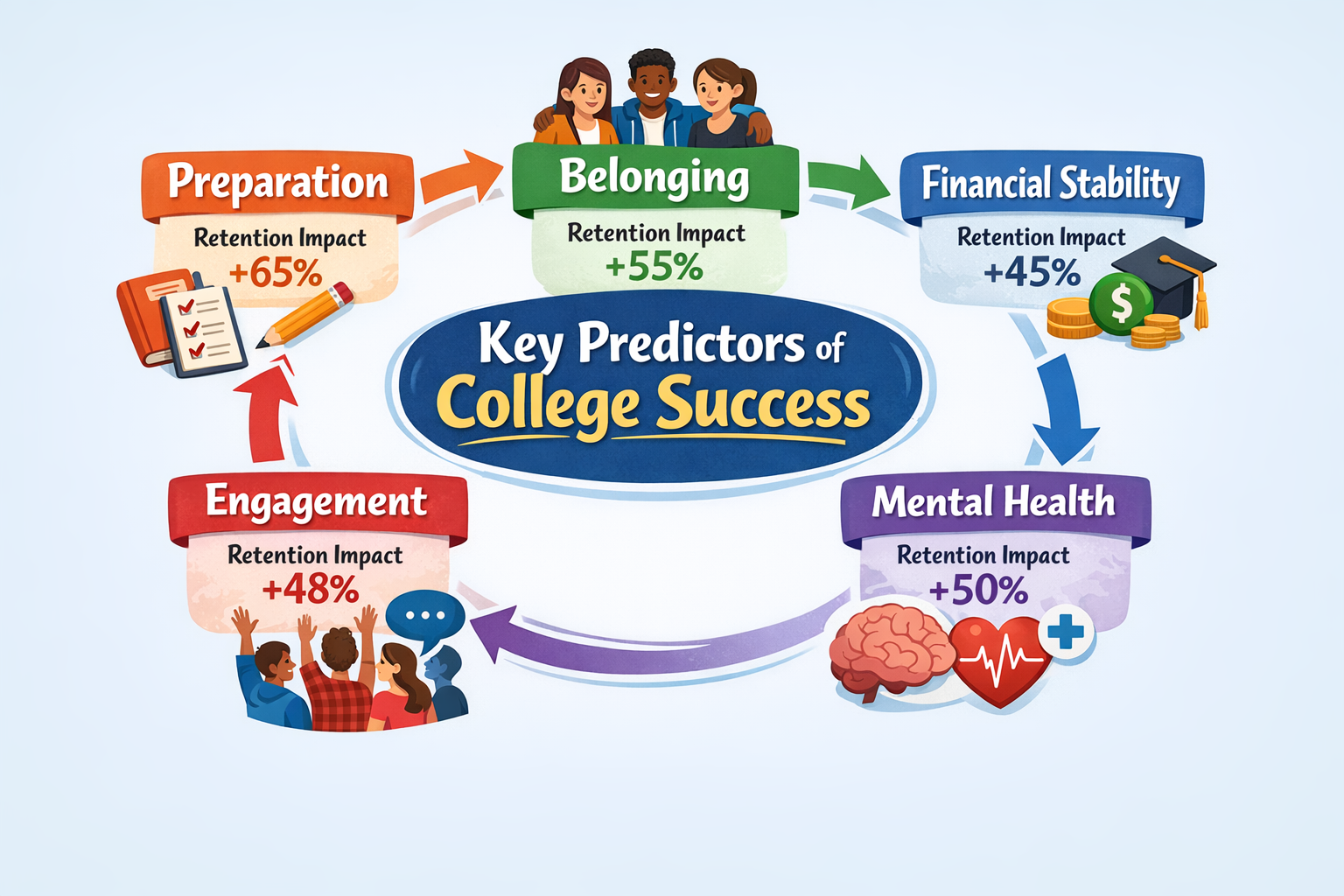

Five Evidence-Based Predictors of Graduation

Research tracking student cohorts over decades has identified these factors consistently across different institution types, regions, and demographics.

1. Academic Preparation (But Not the Kind You Think)

High school GPA remains the strongest single predictor of graduation. Students entering with a 3.0 or higher complete at significantly higher rates. But this isn't purely about intellectual horsepower.

Academic readiness includes invisible procedural knowledge. Knowing how to organize multiple syllabi without someone reminding you. Recognizing when you're actually lost versus temporarily confused. Understanding that asking questions doesn't signal stupidity—it signals engagement. Students from well-resourced high schools often arrive with these capacities already baked in through years of college prep culture. First-generation students and those from under-resourced schools may be equally intelligent but lack the scripts.

Think of it like this: preparation isn't about being smarter. It's about having already practiced the behaviors that college requires before the stakes got real.

2. Belonging: The Factor Nobody Takes Seriously Enough

Students who develop genuine sense of belonging show 7-9% higher persistence rates than those who feel marginal or isolated. That percentage might sound small until you realize it represents thousands of students nationwide who stay enrolled versus leaving.

Belonging transcends friendship. You can have roommates you like and still feel like an imposter in classrooms. Real belonging means feeling legitimately part of the academic community—that you deserve space in seminars, that your contributions matter, that someone would notice your absence.

The effect amplifies for underrepresented students. When you're one of three Black students in a 200-person lecture hall, or the first in your family to attend college, or navigating campus while managing a disability, belonging becomes harder to establish and more critical to persistence. Students who don't find their community within the first six weeks start questioning whether college is "for people like them." That internal narrative drives departures more effectively than academic failure ever could.

3. Financial Reality: It's About Uncertainty, Not Just Poverty

Financial stress absolutely impacts completion. But research reveals something more nuanced than "poor students drop out more." Students with clear, predictable costs and stable aid packages persist at higher rates than those facing constant financial surprises—regardless of absolute family income.

A middle-class student whose parents lost health insurance mid-semester may face higher dropout risk than a lower-income student with comprehensive aid. Emergency expenses create the most dangerous moments. A $500 car repair forces an impossible choice: fix transportation to campus or buy textbooks. Medical bills, family crises, unexpected housing costs—these push students out mid-semester, often when they're otherwise on track academically. Understanding college student basic needs insecurity is crucial for addressing these challenges.

Campuses with emergency grant programs (typically $300-1,000 for unexpected costs) see measurable retention gains. They're not eliminating poverty. They're preventing specific crisis moments from derailing enrollment during the vulnerable window before a student has built enough investment to push through hardship.

4. Mental Health: The Completion Gap Nobody Wants to Discuss

The Healthy Minds Study surveys over 80,000 college students annually (with cumulative data exceeding 300,000 participants over time). Roughly 40% report symptoms of anxiety or depression in any given year. Untreated mental health challenges correlate strongly with lower GPAs and higher dropout rates.

But students who access support services show comparable outcomes to students without mental health challenges. Read that again. The problem isn't anxiety or depression—it's the stigma preventing help-seeking.

What actually works: normalizing counseling as routine maintenance (not crisis response), training faculty to recognize early distress signals, creating peer support networks, ensuring waitlists don't stretch to six weeks when a student finally gets courage to ask for help. When mental health support becomes genuinely accessible rather than theoretically available, the completion gap largely disappears.

5. Engagement: Your Safety Net When Other Things Slip

Students involved in even one regular campus activity—intramural sports, student government, campus jobs, academic clubs—graduate at higher rates than disconnected peers. This holds even after controlling for initial academic preparation.

The mechanism is redundancy. If your organic chemistry class is destroying your confidence, but you're thriving as a resident advisor or finding purpose in the environmental club, you've got a reason to stay enrolled. Multiple connection points mean struggling in one area doesn't erase your entire college identity.

The research on employment reveals interesting nuances. Working 10-15 hours weekly on campus correlates with slightly better outcomes than not working at all—probably because campus jobs build institutional connections and force time management skills. It's only when students work 20+ hours (particularly off-campus) that academic performance tends to decline under the weight of competing demands.

Puncturing Common Myths With Data

Understanding the science of student success means recognizing which factors are overrated.

Myth: SAT/ACT scores are destiny

Once you account for high school GPA, standardized test scores add only about 15% additional predictive power to college outcomes. Many selective institutions went test-optional and haven't seen performance declines. The tests measure something—but not the qualities that actually drive degree completion.

Myth: Changing majors derails graduation

Approximately 30% of students change majors at least once. Early switchers (freshman/sophomore year) show similar completion rates to students who never change. Only very late major changes (junior/senior year) correlate with extended time to degree. Students shouldn't feel imprisoned by their initial choice—exploratory switching is normal and rarely harmful.

Myth: Difficult courses cause dropout Students who challenge themselves academically—taking honors courses, pursuing rigorous majors, engaging in undergraduate research—often show higher completion rates. The key variable isn't rigor but whether adequate support accompanies difficulty. You can maintain high standards if you also provide robust tutoring and advising infrastructure.

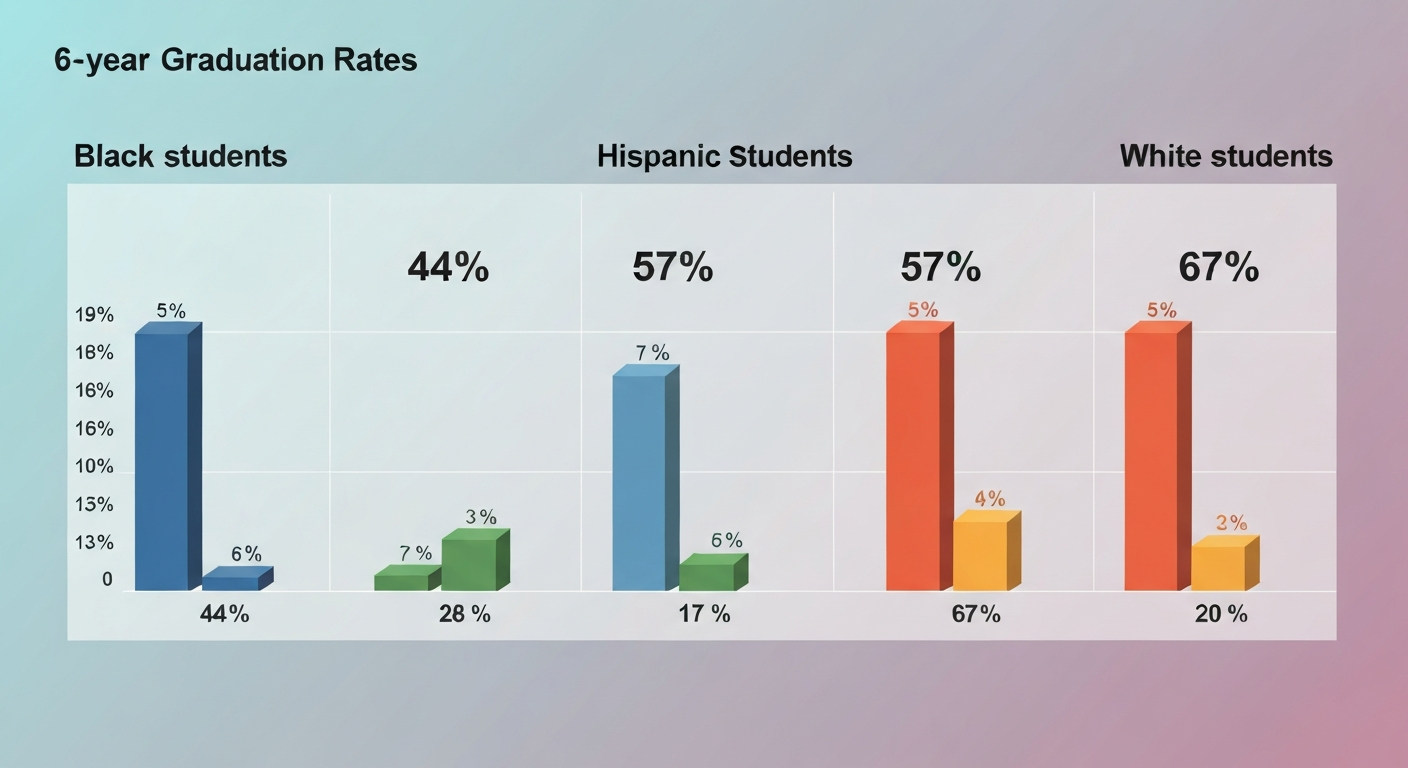

The Uncomfortable Truth About Completion Gaps

The data on student success becomes uncomfortable when you examine demographics.

Six-year graduation rates at four-year institutions:

Black students: ~44%

Hispanic students: ~57%

White students: ~67%

First-generation students complete at rates roughly 10 percentage points lower than continuing-generation peers. Low-income (Pell-eligible) students show similar gaps.

These disparities don't reflect individual preparation or motivation. They're systemic—reflecting differences in high school resources, family wealth available for emergencies, campus climate experiences, access to faculty mentorship from people who share backgrounds, and whether institutions have invested in culturally responsive support rather than expecting assimilation.

Programs that actually close equity gaps include:

Summer bridge programs providing academic and social integration before fall semester

Cohort-based learning communities for first-generation students

Dedicated advisors trained in first-gen and underrepresented student experiences

Emergency aid funds specifically for unexpected costs

TRIO programs (federally funded support for disadvantaged students)

Supplemental Instruction in gateway courses with historically high failure rates

But these require sustained institutional commitment and funding, not just performative diversity statements.

Why Your College Type Matters More Than You Think

Completion varies dramatically by institution:

| Institution Type | 6-Year Graduation Rate | Primary Student Population |

| Highly selective (admit <25%) | 85-90% | Students arriving already prepared; substantial resources |

| Less selective public universities | 50-60% | First-generation, working students; more resource constraints |

| Community colleges (associate degree) | ~40% | Part-time students, working adults, transfer-focused |

| Residential campuses | ~70% | Fewer competing demands (employment, family, transportation) |

| Commuter campuses | ~55% | More external barriers to full engagement |

These aren't purely quality indicators. Completion rates partly reflect demographic sorting—who enrolls where based on geography, cost, and admissions selectivity. Highly selective institutions succeed partly through achievement and partly by admitting students who arrive with advantages already baked in.

Understanding institutional differences matters when evaluating your own situation. If you're attending a less selective public university while working 25 hours weekly and supporting family, you're navigating objectively harder conditions than someone at a residential selective college whose biggest challenge is choosing between three campus activities.

Warning Signs: When to Worry About Your Own Success

Research on early intervention identifies red flags that precede academic crisis:

Academic Disengagement:

Missing 20%+ of classes in any course

Not completing first assignments by week 3

Avoiding office hours when confused

Studying alone rather than with classmates

Social Isolation:

No regular campus activities or involvement

Difficulty naming three people in your major

Spending most time off-campus or in your room

Feeling like you don't belong in college spaces

Financial Stress Signals:

Working 20+ hours weekly while full-time enrolled

Delaying textbook purchases due to cost

Skipping meals to save money

Constant worry about unexpected expenses

Mental Health Decline:

Persistent hopelessness lasting 2+ weeks

Difficulty concentrating on previously manageable tasks

Sleep disruption (insomnia or sleeping excessively)

Withdrawal from previously enjoyed activities

Thoughts that "everyone would be better off without me"

If you're experiencing multiple warning signs, act now—don't wait for crisis. Explore CampusMind's self-assessment tool to evaluate where you stand and what specific resources might help.

Applying Research to Your Own Persistence

So what should students actually do with this information?

Build your support network proactively. During the first week, identify: your academic advisor's office and walk-in hours, the tutoring center location and schedule, where counseling services operate and how to book appointments, at least one campus activity meeting time. Students who map resources before needing them actually use those resources during challenges. Those who don't know struggle silently until problems become catastrophic.

Monitor your engagement religiously. Monthly check: Are you attending class consistently? Have you joined one organization? Can you name three classmates in your major and contact them for study help? Are you using office hours when confused? If you're answering no to multiple questions, that's data telling you to course-correct before grades reflect disengagement.

Get financially organized immediately. Understand your complete aid package and when bills come due. Investigate emergency resources before crisis: many campuses offer $300-1,000 emergency grants for unexpected costs, but students often don't learn about them until after they've already withdrawn. Know your options while you're still enrolled and making rational decisions rather than panic moves.

Normalize using mental health resources. Universal stress in college is normal. Persistent overwhelm, hopelessness, or inability to function signals something more serious. Using counseling doesn't mean you're failing—data shows students who seek support perform better academically. Many campuses now offer drop-in hours, group therapy focused on academic stress, and apps for between-session support.

Take advantage of assessment tools. Self-awareness creates intervention opportunities. Tools measuring engagement, wellbeing, and academic habits help you spot concerning patterns before they show up on transcripts. CampusMind offers evidence-based assessment designed around retention research, helping you identify strengths and gaps systematically rather than intuitively.

What Colleges Are Learning From Retention Science

Institutions increasingly deploy predictive analytics to identify at-risk students early. Modern early alert systems integrate:

Learning management system data (login frequency, assignment completion)

Class attendance patterns (often tracked through campus WiFi or learning platforms)

Engagement metrics from campus activities and services

Financial aid status changes indicating new stressors

But prediction without human intervention is useless. Effective programs pair algorithmic flags with trained advisors or peer mentors reaching out proactively. That personal contact—someone noticing and caring—often provides the tipping point between staying and leaving.

First-year programs are being redesigned around evidence. More institutions now require first-year seminars, offer living-learning communities, and extend orientation programs beyond a weekend. They're investing in peer mentoring because students often trust other students more readily than administrators.

Financial aid offices are shifting from reactive processing to proactive support. Trends include emergency grant programs, radical transparency about total attendance costs before enrollment, and simplified aid communications reducing confusion that triggers departure.

Counseling centers are expanding staff, though demand still outpaces capacity on most campuses. Some institutions now embed counselors directly in academic departments or residence halls, reducing access barriers for students who need help but won't walk across campus to an unfamiliar building.

The Bottom Line on Student Success Data

After analyzing millions of student records and hundreds of retention studies over decades, the science points to a consistent message: completing college isn't about being naturally gifted. It's about building appropriate supports, maintaining engagement through inevitable rough patches, accessing resources during struggles, and—crucially—feeling legitimate in academic spaces.

For students facing challenges:

Struggling to connect? Actively seek communities through clubs, campus employment, living-learning programs, or identity-based student organizations

Financial stress mounting? Talk to financial aid before crisis, investigate emergency fund eligibility, consider reducing course load rather than withdrawing completely

Feeling disengaged? Join one activity this week, attend office hours, initiate study groups with classmates—engagement is a behavior you can change

Mental health suffering? Use counseling services while problems are still manageable rather than waiting for crisis

For parents supporting students: The most valuable support isn't constant grade monitoring. It's helping your student understand these evidence-based success factors and encouraging proactive resource use. Ask about connections and engagement, not just GPA. Notice withdrawal or isolation patterns. Validate struggle while emphasizing that seeking help demonstrates strength, not weakness.

The data on student success has given us a roadmap. Completion isn't mysterious anymore. The question is whether students, families, and institutions will act on what research consistently shows.

Disclosure: This article was created by CampusMind, which provides evidence-based student success tools and resources to colleges and universities. While we've synthesized independent research from federal databases and peer-reviewed studies, our platform offers assessment tools and institutional resources designed around these retention principles.

Frequently Asked Questions

What percentage of college students actually graduate on time? Only about 41% of students starting at four-year public institutions complete their bachelor's degree within four years (the "on time" definition). The more commonly cited statistic—62% six-year graduation rate—includes students who take extra semesters or years. Rates vary dramatically by institution type: highly selective colleges show 85-90% six-year completion, while less selective public universities average 50-60%. Community college associate degree completion within three years (150% of program length) hovers around 38%, though many students transfer before completing.

Does working while in college help or hurt my chances of graduating?

It's complicated and depends on hours worked and job location. Working 10-15 hours weekly (especially in on-campus positions) often correlates with slightly better outcomes than not working—probably because campus jobs build institutional connections and force time management discipline. Problems emerge when students work 20+ hours weekly, which correlates with lower GPAs and reduced campus engagement. Off-campus employment creates particular challenges because it pulls students away from the campus community. The key is balancing income needs with engagement requirements rather than viewing all employment as uniformly harmful or helpful.

How do I know if I should change my major or stick it out?

About 30% of students change majors at least once, and early switching (freshman/sophomore year) doesn't harm completion rates. Signs you should consider changing: genuine disinterest in core courses (not just one hard class), career goals that don't align with your current major, or spending more time on electives than major requirements. Signs to stick it out: one difficult course making you question everything, temporary grade struggles that tutoring could address, or wanting to switch because friends are in a different program. Talk to your academic advisor, career services, and faculty in the major you're considering. Strategic early exploration is smart; late panic-switching after junior year can extend time to degree.

What should I actually do if I'm struggling in college right now?

Take action this week—don't wait for grades to reflect struggles. Step 1: Talk to your academic advisor about your specific challenges (they can't help if they don't know). Step 2: Identify the tutoring center or supplemental instruction for your hardest course and attend at least once. Step 3: If you're feeling persistently overwhelmed or hopeless, contact counseling services for screening—many campuses offer same-day crisis appointments. Step 4: Connect with at least one classmate in each difficult course to form study partnerships. Step 5: Assess whether you're working too many hours or dealing with financial stress that emergency aid could address. Early intervention prevents small problems from becoming catastrophic. Resources exist to help—the challenge is usually accessing them before you've already decided to leave.

Do first-generation college students really have lower graduation rates?

Yes, and the gap is substantial—first-generation students complete degrees at rates roughly 10 percentage points lower than continuing-generation peers with similar academic preparation. This reflects systemic differences: less familiarity with college navigation, fewer family members who can advise on everything from choosing classes to understanding financial aid, potential need to work more hours, and campus cultures often built around assumptions of prior college knowledge. However, programs specifically designed for first-gen students (summer bridge programs, first-gen learning communities, dedicated advisors) significantly reduce these gaps. If you're first-gen, seek out identity-based resources explicitly designed to support students navigating college without family roadmaps—you're not alone, and specialized support really works.

Expertise, Experience, Authority, and Trust

This article synthesizes peer-reviewed research from longitudinal studies tracking student outcomes, including the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center's annual cohort persistence reports, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Beginning Postsecondary Students studies, and the Healthy Minds Network's ongoing survey of college student mental health. Additional research comes from landmark studies by scholars including Vincent Tinto (integration theory), Terrell Strayhorn (belonging research), Clifford Adelman (academic preparation), George Kuh (high-impact practices), and Sara Goldrick-Rab (financial barriers). CampusMind specializes in evidence-based student success initiatives, working directly with colleges and universities nationwide to implement retention strategies grounded in this research base. Our team continuously monitors emerging longitudinal data and meta-analyses to update approaches as new evidence becomes available.

Cited Works

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center — "Persistence and Retention – 2024." February 2024. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/PersistenceRetention2024.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics — "Undergraduate Retention and Graduation Rates." NCES Fast Facts, 2024. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=40

National Center for Education Statistics — "Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS)." NCES 2018-434, 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018434

Adelman, Clifford — "The Toolbox Revisited: Paths to Degree Completion From High School Through College." U.S. Department of Education, 2006. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/toolboxrevisit/toolbox.pdf

Strayhorn, Terrell L. — "College Students' Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for All Students, 2nd Edition." Routledge, 2019. https://www.routledge.com/College-Students-Sense-of-Belonging-A-Key-to-Educational-Success-for-All/Strayhorn/p/book/9781138238558

Healthy Minds Network — "The Healthy Minds Study: 2023-24 Data Report." University of Michigan School of Public Health, 2024. https://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/data-for-researchers/

Goldrick-Rab, Sara — "Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream." University of Chicago Press, 2016. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo22281946.html

Kuh, George D. — "High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter." Association of American Colleges & Universities, 2008. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/HIP_tables.pdf

Tinto, Vincent — "Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition, 2nd Edition." University of Chicago Press, 1993. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/L/bo3630345.html

Perna, Laura W. (Editor) — "Understanding the Working College Student: New Research and Its Implications for Policy and Practice." Stylus Publishing, 2010.

Hiss, William C. and Franks, Valerie W. — "Defining Promise: Optional Standardized Testing Policies in American College and University Admissions." National Association for College Admission Counseling, 2014. https://www.nacacnet.org/globalassets/documents/publications/research/defining-promise-2014.pdf

Opportunity Insights — "The Effect of SAT and ACT Scores on College Grades." Harvard University, January 2024. https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/SAT_ACT_on_Grades.pdfInstitute for Higher Education Policy — "Student Experience and Belonging: Strong Outcomes." Research Brief, 2023. https://www.ihep.org/publication/student-experience-and-belonging-strong-outcomes/