For first-generation college students, the campus map looks different. There's no family playbook for navigating FAFSA renewals, no casual advice about how to approach a professor during office hours, no reassuring stories about surviving that brutal first semester. The path to graduation is navigated without the institutional knowledge that continuing-generation students often take for granted.

The research confirms what many already sense: first-generation students leave higher education at significantly higher rates than their peers. But the reason isn't ability. First-gen students don't struggle because they lack intelligence or motivation—they leave because systems weren't designed with them in mind.

The institutions seeing measurable gains in first-gen retention aren't waiting for students to figure it out alone. They're building intentional support structures—bridge programs that start before day one, mentoring relationships that create the social capital first-gen students often lack, and data systems that identify disengagement before it becomes departure.

This guide breaks down what the research says, what's actually working at the operational level, and how campus leaders can move from awareness to action.

Key Takeaways:

First-generation students face compounding challenges including financial strain, cultural navigation gaps, and weaker institutional connections—not deficits in ability

The first 100 days are critical: students who don't establish peer and faculty connections during this window are significantly more likely to leave

Summer bridge programs consistently show retention improvements of 8–12 percentage points among participants

Structured peer mentoring with trained upper-class mentors who share similar backgrounds shows the strongest outcomes

Institutions that set explicit, public retention targets for first-gen students create accountability and focus resources where they matter most

First-Generation Student Challenges: What the Data Actually Shows

Before designing interventions, campus leaders need to understand the specific friction points first-gen students encounter. The challenges extend beyond academics into cultural navigation, financial pressure, and institutional belonging.

The Numbers Behind the Gap

First-generation college students—typically defined as those whose parents did not complete a four-year degree—make up roughly one-third of all undergraduates in the United States [1]. Yet their graduation rates lag significantly behind their continuing-generation peers. Research from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that first-gen students are nearly four times more likely to leave college after the first year compared to students whose parents hold bachelor's degrees [2].

The gap isn't about capability. First-gen students often arrive with strong academic records but face a constellation of challenges that compound over time:

Financial strain: Many work significant hours while enrolled, limiting time for study and campus involvement

Cultural navigation: Unwritten rules about professor relationships, study groups, and campus resources feel foreign—what researchers call the "hidden curriculum"

Family obligations: First-gen students frequently manage responsibilities at home that peers don't face

Imposter syndrome: Without family role models, many question whether they truly belong

The Hidden Curriculum Problem

The "hidden curriculum" represents the unspoken rules of college success that continuing-generation students absorb through family experience. First-gen students often don't know:

That syllabi are negotiable documents (late policies, participation expectations) that can sometimes be discussed with professors

How to decode professor feedback or understand what "office hours" actually means in practice

That campus resources like tutoring centers, writing labs, and counseling services exist specifically for students—and using them is normal, not a sign of weakness

How to navigate financial aid verification processes that require documentation many families don't readily have

These knowledge gaps create friction at every turn. A continuing-generation student with a question about financial aid might text a parent who went through the same process. A first-gen student may spend hours searching websites, miss deadlines, or simply give up.

Why Early Academic Setbacks Hit Harder

A single failed exam or disappointing GPA carries different weight for first-gen students. Research published in the Journal of Higher Education found that early academic setbacks—even minor ones—disproportionately predict dropout among first-generation students compared to their peers [3].

Without the generational knowledge that a rough first semester is survivable, many interpret struggles as confirmation they don't belong. A continuing-generation student who fails a midterm might hear from a parent: "I failed my first chemistry exam too. Here's how I recovered." A first-gen student often interprets the same failure as evidence that college wasn't meant for them.

The first 100 days of college are particularly critical. Students who don't establish connections to peers, faculty, or campus resources during this window are significantly more likely to leave. For first-gen students navigating unfamiliar terrain, those connections often don't happen organically—they require intentional institutional design.

Pre-Matriculation Strategies: Why Summer Bridge Programs Yield Higher Retention

The most effective retention strategies for first-generation students don't wait until problems emerge. They start before the first day of class, building academic confidence and social foundations during the transition period.

The Evidence for Summer Bridge Programs

Summer bridge programs—intensive pre-college experiences that introduce students to campus life, academic expectations, and support resources—consistently show positive outcomes for first-gen students. A study of 24 bridge programs across the country found participants had first-year retention rates approximately 8–12 percentage points higher than similar students who didn't participate [4].

What makes bridge programs effective isn't just the academic preparation. It's the social foundation they build. Participants arrive on campus already knowing other students, already familiar with where the tutoring center is, already having met faculty members who can serve as early advocates. They start with a community rather than building one from scratch during the chaos of orientation week.

Effective bridge program elements include:

Academic skill-building workshops (time management, note-taking, college-level writing expectations)

Campus resource tours with actual practice accessing services—not just walking by buildings

Peer mentor introductions that continue into the fall semester

Family orientation components that bring parents into the conversation about supporting students appropriately

Social activities that build cohort identity before fall semester begins

Moving Beyond One-Shot Orientation

Traditional orientation programs pack information into a few overwhelming days. First-gen students benefit from extended orientation models that unfold over weeks or even the full first semester.

Some institutions are experimenting with "First-Year Experience" courses specifically designed for first-generation students. These credit-bearing classes combine academic skill development with peer community building, and research suggests they improve both GPA and retention outcomes [5]. The key difference: instead of a single information dump, students receive ongoing touchpoints and normalized learning curves throughout their critical first semester.

Extended orientation components that show promise:

Weekly small-group check-ins during the first six weeks

"Hidden curriculum" workshops that explicitly teach unspoken college norms

Peer mentor pairings that extend through the full academic year

Regular connection points with academic advisors (not just registration meetings)

Peer and Faculty Mentoring: Building the Social Capital First-Gen Students Lack

If first-generation students lack inherited social capital, institutions can help them build it. Mentoring relationships—with peers, faculty, and staff—consistently emerge as one of the strongest predictors of first-gen student persistence.

Why Peer Mentoring Creates Belonging

When a sophomore who was also a first-gen student tells a struggling freshman, "I felt exactly like this last year, and here's what helped me," something shifts. The message isn't coming from an authority figure—it's coming from someone who walked the same path and survived.

Structured peer mentoring programs pair first-gen students with upper-class mentors who share similar backgrounds. The most effective programs go beyond casual check-ins to include:

Regular one-on-one meetings with guided conversation topics (not just "how's it going?")

Group activities that build cohort community across mentor-mentee pairs

Training for mentors on effective support strategies and recognizing warning signs

Connections to campus resources through mentor introductions, not just referrals

Academic support and study group facilitation

Research from the University of Texas at Austin's Project MALES found that peer mentoring programs for first-generation students of color improved first-year retention by over 12 percentage points [6]. The key wasn't just having a mentor—it was having a mentor who could authentically relate to the student's experience.

Opt-in vs. Opt-out mentoring models: Programs that automatically assign mentors (with an option to decline) show higher engagement than those requiring students to seek out mentorship. First-gen students may not realize they need support or may feel uncomfortable asking for it.

Faculty Mentoring That Demystifies Academia

For many first-gen students, professors feel like distant authority figures rather than accessible resources. Faculty mentoring programs can bridge this gap, but they require intentional design beyond "my door is always open."

Effective approaches include:

Faculty-in-Residence programs that bring professors into residence halls for informal interactions

First-gen faculty identification campaigns where professors who were themselves first-generation students share their stories publicly

Research opportunity pipelines that connect first-gen students with faculty mentors through undergraduate research positions—often the first meaningful faculty relationship for many students

Proactive advising models where advisors reach out to students rather than waiting for students to seek help

When first-gen students see faculty members who came from similar backgrounds—and when those faculty explicitly share their journeys—the implicit message is powerful: people like me succeed here.

Staff and Professional Mentoring

Career services, financial aid offices, and student affairs professionals can all serve mentoring functions. First-gen students often lack professional networks and familiarity with career trajectories that continuing-generation students access through family connections.

Connecting first-gen students with staff mentors who can demystify professional pathways addresses a gap that affects outcomes well beyond graduation. A first-gen student may not know what "networking" actually looks like in practice, how to approach an internship search, or what career paths exist in their field of study.

The Sophomore Slump: Retaining First-Gen Students After Year One

Most institutional attention focuses on the first-year transition, but first-gen students face continued challenges into their second year and beyond. The "sophomore slump" hits first-gen students particularly hard as:

Initial support programs often end after freshman year

Major selection pressure increases without family guidance on career implications

Financial aid packages may shift, creating new affordability concerns

Social groups established freshman year may fragment as students move off-campus or change schedules

Strategies for sustained support:

Extending mentoring relationships through sophomore year

Career integration programming that connects major selection to career pathways

Peer study groups within declared majors

Continued check-ins from student success staff, not just during academic crises

Second-year residential or cohort options that maintain community

Institutions that track retention only through the first-to-second-year transition may miss significant attrition patterns among first-gen students in subsequent years.

Leveraging Technology and Real-Time Data for Early Intervention

The most effective retention efforts don't wait for midterm grades to identify struggling students. Modern engagement platforms can provide real-time signals of disengagement—allowing intervention before small concerns become departure decisions.

Moving from Retrospective to Proactive Support

Traditional early-alert systems flag students after they've already failed an exam or stopped attending class. By then, the student may have already mentally checked out. Real-time engagement data can identify concerning patterns earlier:

Declining participation in campus events or activities

Reduced interaction with peer communities

Missed appointments with support services

Changes in app engagement patterns or check-in responses

The goal isn't surveillance—it's creating opportunities for proactive outreach. When a student who was highly engaged suddenly goes quiet, that's a signal for a check-in, not a performance review.

Digital Nudges and Personalized Recommendations

First-gen students often don't know what resources exist or when to access them. Technology can bridge this gap through:

Personalized resource recommendations based on student characteristics and expressed needs

Timely reminders about deadlines, events, and opportunities

Peer connection suggestions that help students build social networks

Low-stakes check-ins that normalize asking for support

The key is making support feel proactive and personalized rather than reactive and bureaucratic. A nudge that says "Students like you found this tutoring workshop helpful before midterms" is more effective than a generic email blast about tutoring availability.

Celebrating First-Gen Success: From Deficit to Resilience Framing

Representation matters. When first-generation students see themselves reflected in campus success stories, belonging becomes more tangible. But the framing matters as much as the visibility.

Asset-Based Approaches to First-Gen Identity

Effective programs shift the narrative from "at-risk" to "resilient." First-gen students bring cultural wealth, determination, and perspectives that enrich campus communities. The challenge isn't fixing students—it's building systems that recognize and leverage their strengths.

The national First-Generation College Celebration, held annually on November 8, has given institutions a platform to publicly honor first-gen students and alumni. But celebrating first-gen identity shouldn't be confined to a single day.

Year-round strategies that work:

First-gen graduate profiles featured on social media, websites, and campus publications

Alumni speaker series bringing back successful first-gen graduates to share their journeys—including the struggles, not just the victories

Visual representation through posters, digital displays, and orientation materials showing first-gen student faces and stories

First-gen honors cords and recognition at graduation ceremonies

"I'm First" campaigns where students, faculty, and staff publicly identify as first-generation

These approaches normalize first-gen identity rather than treating it as a deficit to overcome.

Building First-Gen Community

Some institutions have created first-generation student centers or dedicated spaces where first-gen students can gather, study, and connect. Even without physical space, building community through first-gen student organizations, living-learning communities, or cohort-based programming creates the peer networks that support persistence.

Georgia State University's approach offers a compelling example. By combining data analytics to identify at-risk students with proactive advising interventions, the institution increased its graduation rate by 23 percentage points over a decade—with the largest gains among underrepresented students including first-generation students [7]. Their model demonstrates that institutional commitment, paired with targeted support, can dramatically shift outcomes.

Setting Retention Targets: Creating Accountability That Drives Results

Good intentions aren't enough. Closing the gap for first-generation students requires clear targets, consistent measurement, and institutional accountability.

Disaggregate Your Data

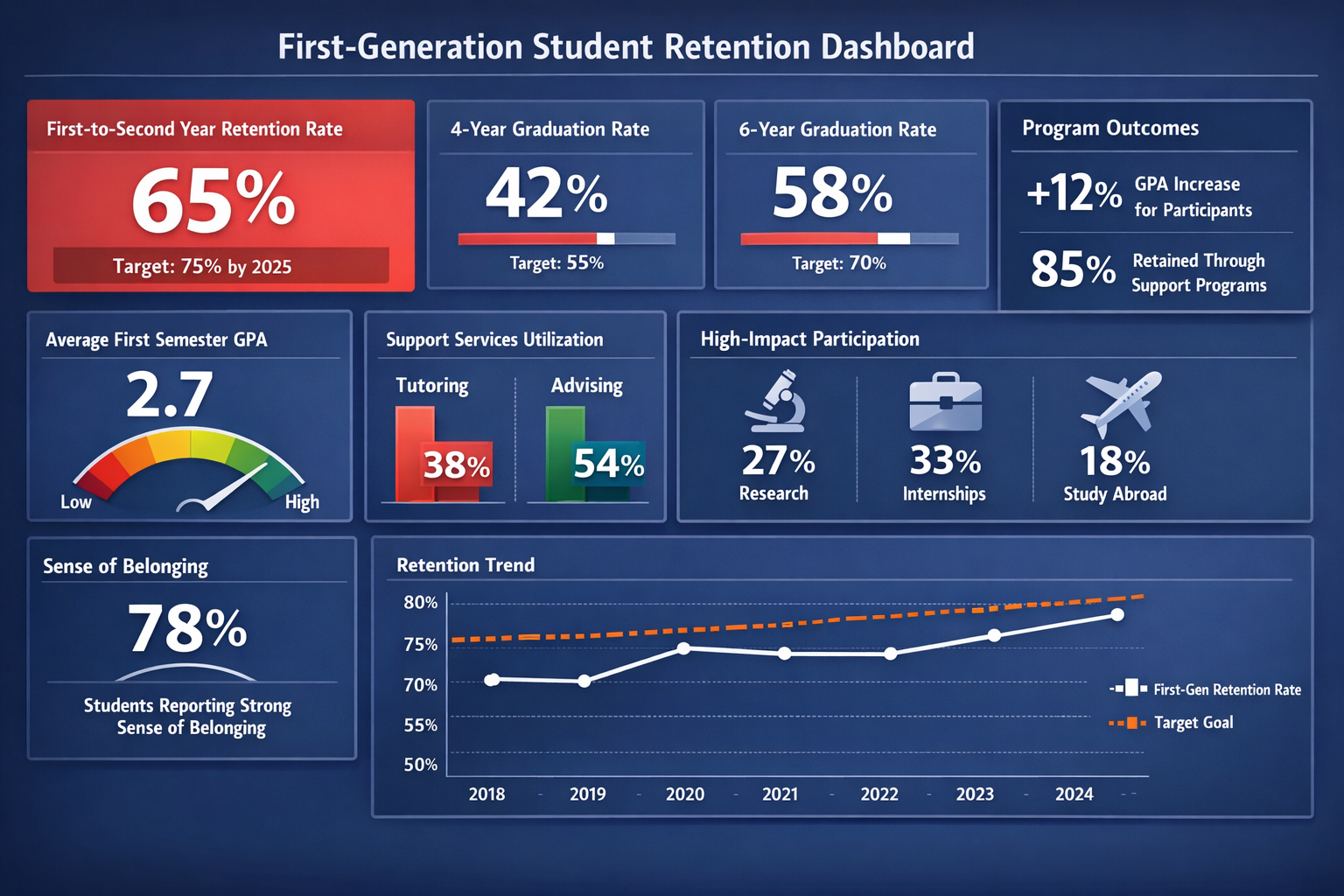

Many institutions track overall retention rates without examining how different student populations are faring. Breaking down retention and graduation data by first-generation status reveals disparities that aggregate numbers hide.

If your institution's overall retention rate is 80% but your first-gen retention rate is 65%, you have a specific problem to address—and a specific metric to improve.

Key metrics to track for first-gen students:

First-to-second-year retention rate

Four-year and six-year graduation rates

Average first-semester GPA

Utilization rates for support services (tutoring, advising, counseling)

Participation rates in high-impact practices (undergraduate research, internships, study abroad)

Sense of belonging scores from student surveys

Set Specific, Measurable Goals

Institutions serious about first-gen student success should set explicit targets. For example: "Increase first-generation student retention from 68% to 75% within three years." Public targets create accountability and focus resources.

The California State University system's Graduation Initiative 2025 provides a model. By setting systemwide goals for eliminating equity gaps in graduation rates—including for first-generation students—the initiative created institutional accountability and catalyzed investment in student success programs [8].

Close the Loop on Interventions

Not every program works equally well. Institutions should evaluate which interventions are actually improving first-gen outcomes and reallocate resources accordingly. This means tracking:

Which students participate in which programs

Retention and GPA outcomes for participants versus non-participants

Student satisfaction and sense of belonging among program participants

Cost per student served and cost per retained student

Data-driven refinement ensures that resources flow to what works—not just what feels good or has always been done.

Practical Next Steps for Campus Leaders

Closing the gap for first-generation students isn't about a single initiative. It's about building an ecosystem of support that meets students where they are.

For immediate implementation:

Audit current programming to identify what specifically targets first-gen students

Disaggregate retention and graduation data by first-generation status

Launch or expand a summer bridge program for incoming first-gen students

Create a peer mentoring program that pairs first-gen students with trained upper-class mentors who share similar backgrounds

Identify and publicly celebrate first-gen faculty and staff who can serve as role models

For longer-term investment:

Establish a first-generation student center or dedicated programming

Implement proactive advising that reaches out to first-gen students rather than waiting for them to seek help

Set public retention and graduation targets for first-gen students

Build family engagement programming that brings parents into the support ecosystem appropriately

Partner with platforms that provide real-time engagement data and early risk alerts

First-generation students arrive at college with determination, resilience, and perspectives that enrich campus communities. Institutions that recognize this—and build systems designed to unlock it—will see the gap close.

Ready to explore how data-driven engagement can support your first-generation students? Book a CampusMind demo call to learn how real-time insights and proactive support can improve retention for your most underserved populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What defines a first-generation college student?

A first-generation college student is typically defined as someone whose parents or guardians did not complete a four-year bachelor's degree. Some institutions use a stricter definition requiring that neither parent attended any college. This status correlates with less inherited knowledge about navigating higher education, fewer professional networks, and additional financial pressures. Understanding how your institution defines first-gen status is important for consistent tracking and targeted support.

Why do first-generation students have lower retention rates?

First-gen students often face compounding challenges: financial stress requiring significant work hours, unfamiliarity with the "hidden curriculum" of college norms, family obligations continuing-generation students don't manage, and fewer built-in support networks. Academic setbacks that continuing-generation students weather more easily can feel like confirmation of not belonging. These factors compound when institutional support systems aren't designed with first-gen needs in mind.

How effective are summer bridge programs for first-gen students?

Research consistently shows that summer bridge programs improve first-year retention for first-generation students, with studies documenting retention increases of 8–12 percentage points among participants compared to similar non-participants. Effectiveness comes from building academic skills, creating peer communities before fall semester begins, and familiarizing students with campus resources in a lower-stakes environment where questions feel safe.

What role do peer mentors play in first-gen student success?

Peer mentors provide relatable support that authority figures often cannot. When mentors share similar backgrounds, they offer practical advice and emotional validation that normalizes the first-gen experience. Effective peer mentoring programs with trained mentors who meet regularly have shown retention improvements of 10% or more. The key is structured programming—not just casual check-ins—with mentors trained to recognize warning signs and connect mentees to resources.

How should institutions measure first-gen student success?

Institutions should disaggregate retention and graduation data by first-generation status, tracking both absolute rates and gaps compared to continuing-generation peers. Additional metrics include first-semester GPA, utilization of support services, participation in high-impact practices like undergraduate research and internships, and sense of belonging survey scores. Setting public targets for first-gen retention creates accountability and focuses institutional resources on closing equity gaps.

Why This Matters: Our Commitment to Student Success

This article draws on peer-reviewed research in higher education, data from national studies including the National Center for Education Statistics, and evidence-based practices documented by student success organizations. CampusMind's approach to student engagement is grounded in behavioral science and informed by ongoing collaboration with campus leaders who work directly with first-generation students every day. Our advisory panels include practitioners with deep expertise in equity, retention, and student wellbeing—ensuring that our platform and content reflect what actually works in supporting underrepresented student populations.

Works Cited

[1] RTI International — "First-Generation Students: College Access, Persistence, and Postbachelor's Outcomes." https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/dmfile/FactSheet-01.pdf

[2] National Center for Education Statistics — "First-Generation Students: Undergraduates Whose Parents Never Enrolled in Postsecondary Education." https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018421.pdf

[3] Ishitani, T.T. — "Studying Attrition and Degree Completion Behavior among First-Generation College Students in the United States." Journal of Higher Education. https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/uhej20

[4] Sablan, J.R. — "Can You Really Measure That? Combining Critical Race Theory and Quantitative Methods." American Educational Research Journal. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/aer

[5] Pascarella, E.T. & Terenzini, P.T. — "How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research." Jossey-Bass Publishers. https://www.wiley.com/en-us

[6] Sáenz, V.B. & Ponjuán, L. — "The Vanishing Latino Male in Higher Education." Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/jhh

[7] Georgia State University — "Student Success Programs." https://success.gsu.edu/

[8] California State University — "Graduation Initiative 2025." https://www.calstate.edu/graduationinitiative2025